I’m David, and my goal with this repository is to demystify the word protocols in enven more detail then my previous article called IoT-Raw-Sockets-Examples, and proving that there is nothing to hard to learn. We just need to pass through the unknown...

Before you start, I recommend that you read the previous article, in which I explain sockets in detail, using Particle and NodeJS. We're going to use sockets in this one, too, but this time, we're going to focus on how to work with a binary protocol. We're also going to craft our own ICMP header, and read the response from the remote host.

I know that the words protocol, binary, and crafting - might sound hard or complicated, but my point is that this is not the case.

How to understand a header specification

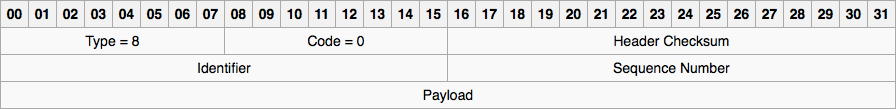

If you visit the wikipedia page that covers the ICMP protocol, you’ll find this table that describes the header that needs to be sent over the wire to actually make a Ping request.

Let's start by understanding that we are talking about a binary protocol, meaning we are going to send bytes, which are numbers. Those numbers are as is, they are not an ASCII representation of the keyboard character set - for example.

One byte is 8 bits, which means that an integer of value 8 is 00001000. This is not an ASCII 8, the same letter that you are reading right now. This means that we can’t type just the number 8 on our keyboards and send it out.

Pre flight check

To make our life easier, we're going to write our data in Hex (short for Hexadecimal). This format is way more manageable, because instead of writing numbers as integers, we're going to write an integer in a set of 2 characters. 38450 becomes 0x9632, and we can display this as 96 32 (where the 0x is just a way to mark a set of character as Hex), inserting a space every 2 numbers, because 2 numbers in Hex are one byte. This makes it way easier to debug in the console, and read.

Let's break down the table above

It starts with 00 to 31, which means each row consists of 32 bits, which, if we divide by 8 bits, gives us 4 bytes. The table has 3 rows, so in total we are going to send 12 bytes.

The first row consists of 3 data sets: 1 byte for the type (uint8_t); 1 byte for the code (uint8_t); and 2 bytes for the check sum (uint16_t). This could look something like this: 08 00 FF F7.

The second row has 2 bytes (uint16_t) for the identifier, and 2 for the sequence number. As an example: 09 A0 00 01.

The third row is the payload, which is optional. You could send some random data, and the router would have to return that data back to you. It's useful if you want to be sure that data is not being lost along the way. But in our example, we are not going to use this option.

Why we're using NodeJS for this project

This project has NodeJS to show the difference between a low level language and a high level one. NodeJS can handle sockets very well. However, there are different types of sockets that live in different parts of the OSI model. As you can see from the Wikipedia table, TCP and UDP lives on the fourth layer of the model, which NodeJS can handle. But from the Examples column, you can see that ICMP lives on the third layer, and NodeJS can’t reach this layer. But we will still be able to ping from NodeJS - how? I’ll explain later.

The file structure

As you can see from the repository, there are two folders: C and NodeJS. Each folder has three files that are named using the same format to help you to easily match each example from one language to the other:

- pingWithBareMinimum: This file will create a PING with the bare minimum code needed to do so, so we can focus on understanding how to build our own header, and get a result from the remote machine.

- pingWithStructResponse: This file is where we are going to apply our knowledge from before. This time, however, we're going to store the result in a C struct, and a buffer in the case of NodeJS

- pingWithChecksum: This is where we implement everything, so we can actually send a proper ping with changing data.

Let's start with C

Section 3 in the pingWithBareMinimum.c file is the part that interests us the most. Here is where we actually create the ICMP header. First of all, we describe a struct, which is our header - the same header that I described above from the image. To make sure we are on the same page:

- uint8_t: means 8 bits, which is 1 byte

- uint16_t: means 16 bits, which is 2 bytes

- uint32_t: means 32 bits, which is 4 bytes

Once we have our struct done, we basically just create our own data type. That's why we're typing icmp_hdr_t pckt;, where icmp_hdr_t is the type that we created. We then create a variable of this type.

The following code just uses the newly created struct, and adds the required data. One important thing to notice is the data field. We don’t need to write 4 zeros to fill the 32-bit space. This is because, when we create the variable with our struct, the memory is already assigned, since we explicitly sad: uint32_t data;, and the compiler knows that we are using 4 bytes of memory.

The next part is the IP header, which, as you can see, also uses a struct. But this time, we are not creating it, because someone else already did it in one of the libraries that we imported. We could make our own; we would just need to follow the IP protocol. But we're lazy, so let's use someone else's creation 😎.

Once we have all of this, we can use our socket that we created at the beginning of the file and send our header. If we did everything correctly, in Section 4 we'll get a nice replay from the remote host.

Read the replay

Until now, we've created the most basic ping possible. In this section, we're going to focus on the response; more specifically, how to get the response and map it to a struct so we can have easy access to the data within our code. Lets open the pingWithStructResponse.c file and get down to it.

Scroll down to Section Four, and you’ll see that there is a new struct in place. Here, we are again telling the compiler how much space are we going to need and how it should be divided.

On line 110, you can see that we are creating a variable using our struct, and in the line below, we are casting the buffer to our variable, starting at the 20th byte. Since everything before the 20th is data related to the IP and TCP protocol, which we don’t care about, we just want to see what message we have from the remote host.

After mapping the data to a structure, you can see in the next line that we are able to log each piece of information very easily.

All in

We can make a request, and we can easily read the reply. But we can’t yet fully use the whole protocol, since it lacks the checksum function that should calculate the check sum. Right now, we keep sending a fixed checksum, since we don't pass the identifier or the sequence_number. Now is the right time to keep improving our code.

Regarding the new variables from file pingWithChecksum.c:

- identifier: A number that, if sent, will be sent back to us. The idea is that we can identify whether the ping came from our app, or someone else's. Meaning that in the replay we could filter the incoming ping responses, and only show ours.

- sequence_number: A number that is going also to be sent back to us. It is useful to see if we've lost some packets, because the idea is to increment this number whenever we make a ping request.

Adding these values will make each request unique. Thus, we need to calculate the checksum; otherwise the ping will be stopped within our network by our home router.

The checksum works in the following way: it grabs two bytes at the time, and sum them together to the previous value. If there is some left overs, meaning the headers isn't dividable by two. Then the if statement after the loop will add the last value. But since we are dealing with a 12 byte header, that code will never be executed.

The difference between NodeJS and C

Until now, we've covered only the C code in this project, but why even put NodeJS here? I like to see what the limits of this environment are, and then use it as an example to show the difference between a low-level language like C, and a higher-level language like NodeJS.

Since the file names are exactly the same - as far as the format - you can easily open the matching files, and see the differences. For example, it is much easier in C to create a binary header, thanks to structs, and also to map a buffer to each struct to have easy access to the data.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, we know that NodeJS works on a higher layer of the OSI model. Because of that, yes, we wrote our new header code to make a ping request in NodeJS, but we had to use an external module called raw-socket, which is basically C code wrapped in Javascript for easy use in NodeJS. You can learn how to use C code in NodeJS in another article that I wrote, title: How-to-Deconstruct-Ping-with-C-and-NodeJS.

This also means that this module might work differently under different systems, since it uses the sockets that the systems is providing. The author of this module, of course, tried to make sure it would work in as many places as possible, but different systems - like Windows and MacOS - don’t adhere to the POSIX standard. I highly recommend reading the project README.md file to learn more.

Was it that bad?

And you made it! :) I hope this article was clear and to the point, and that protocols don't scare you anymore! By now, this word should make you excited at the prospect of learning how a piece of software is able to communicate with another remote device, whether it's a computer, IoT, or even a radio.

As always, if you would like me to explain something in greater detail, please feel free to ask me!

Thank you

I want to thank all of the good people who helped me with this project, including:

- Tomasz Wątorowski: For helping me understand C even better.

The End

If you've enjoyed this article/project, please consider giving it a 🌟. Also check out my GitHub account, where I have other articles and apps that you might find interesting.

Where to follow

You can follow me on social media 🐙😇, at the following locations:

More about me

I don’t only live on GitHub, I try to do many things not to get bored 🙃. To learn more about me, you can visit the following links:

David Gatti

David Gatti

Discussions

Become a Hackaday.io Member

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.