Is this really state of the art, measuring used fuel just by time? Are there no fuel level sensors available just like in any car, or at least flow meters which measure fuel usage?

If my life depends on not running out of fuel it seems quite disturbing to just rely on absolutely constant fuel usage over time during the flight.

— martin

Great questions. Using time is definitely not state of the art technology, and you're quite right that running out of fuel in an aircraft means you're gonna have a bad time.

From my flight training, experience and some research, I would say that the use of time comes down to operational aspects more than a lack of technology. Specifically, managing the phase of flight where accurate fuel information is the most critical: pre-flight planning.

When is fuel information relevant?

The amount of fuel onboard is arguably most relevant when you can add more - before you ever start the engine. Before you get into an aircraft, you want to know you have enough fuel for your intended trip, plus further flight to alternative/backup destinations, plus any legally required reserves (30 minutes for visual flight during the day in New Zealand). It's nice to confirm enroute with technology that everything is going to plan, but you'd never take off in an aircraft without redundant checks ensuring you have enough fuel for the time you want to fly. That said, searching the NTSB aviation database for "fuel exhaustion" returns 2,718 results for the period 1970 - 2017; one per week on average.

Part of the pre-flight inspection for most light aircraft includes 'dipping' the tanks with a calibrated stick to check the volume of fuel in the each tank. Larger aircraft use electronic gauges to check fuel quantity or weight during pre-flight, but even airliners still have physical dipstick devices for redundancy. Personally I don't check the fuel gauges in the cockpit until I'm in the process of starting the engine.

Calculating fuel time

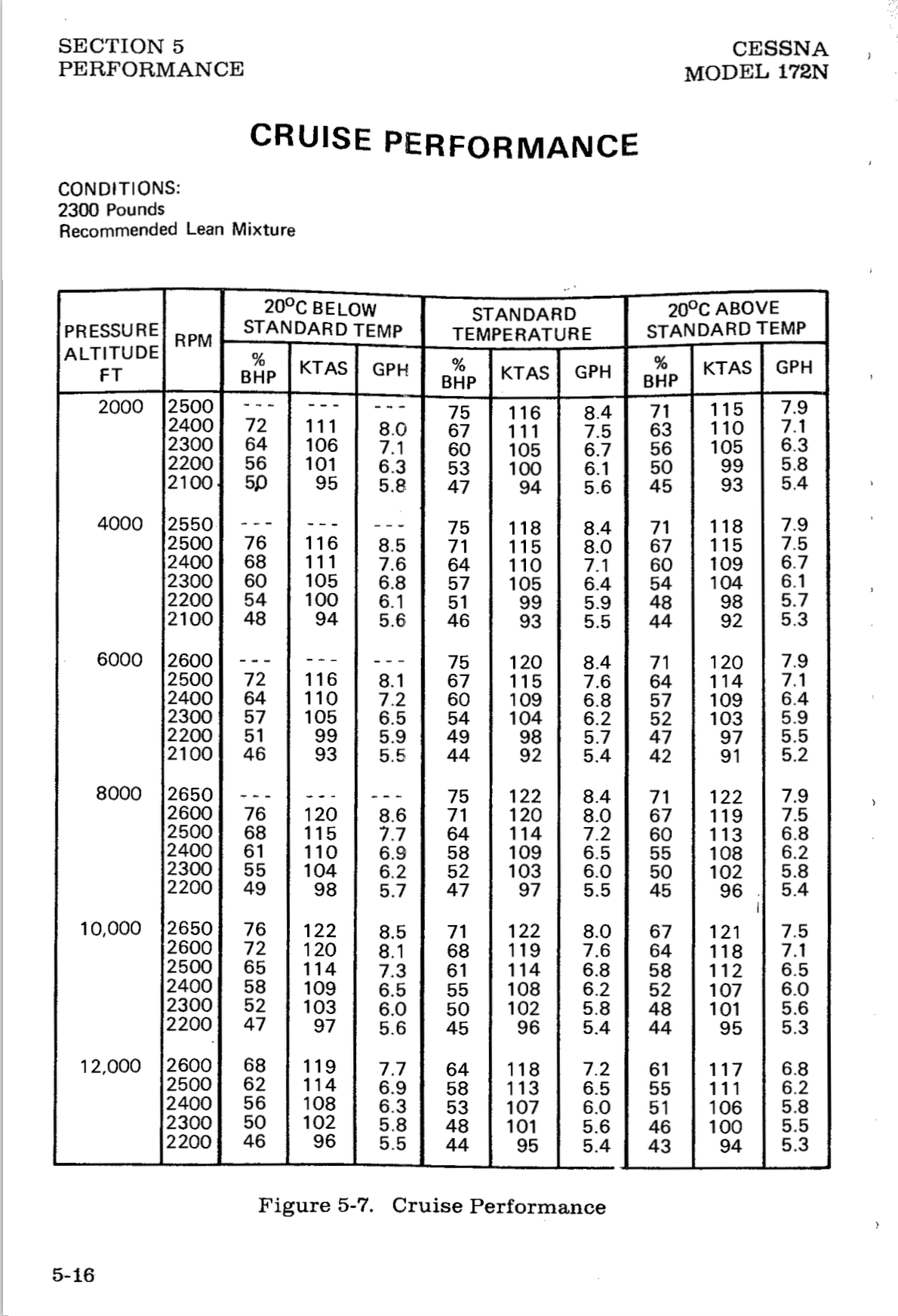

"Half a tank" or any specific volume of fuel won't get you a reliable distance in an aircraft like it does in a car, so you can't just jump in and go. The amount of time required to travel a planned route is calculated by determining the ground speed for each portion of the trip based on intended cruise speed, altitude and forecast wind velocities

While it is possible to go into detail calculating different burn rates in different phases of the flight based on engine RPM and time spent climbing, having more fuel is almost always better. Hence, in practice it's easier and safer to base fuel requirement calculations on a constant high or maximum burn rate (especially for training operations), rather than trying to squeeze a little more load on board in place of fuel. If you're flying long distances at high altitudes you'd factor that in, but for a weekend warrior doing short trips, taking extra fuel isn't a problem.

If you ever got into a situation where you were running out of fuel time that was calculated using a high or maximum burn rate, you'd be unlikely to be complaining about the extra litres you might have available to get the plane down safely.

Fuel level sensors

To answer your second question, light aircraft do have car-like fuel level sensors in each tank, but they're generally not accurate enough to rely on as more than a cross-check against other calculations while in flight. Fuel level sensors rely on the aircraft being level and in balance (not yawing relative to the flight path, which can push fuel to either end of the tanks). Since an aircraft can rotate in space, these aren't always going to display correctly.

Digital/"glass" cockpits (like the Garmin G1000) tend to have numeric display of fuel quantity, which is more accurate to read than analogue gauges, but should still only be used as one of many sources of information - not used as the sole indicator like you do in a car.

Fuel management isn't so much about accurate gauges as it is planning though. The most accurate and readable fuel gauge in the world isn't any better than a crusty analogue one if it's telling you you're running out of fuel. The Pilot's Operating Handbook for a Cessna 182 with glass cockpit published in 2004 echoes this in its section on fuel systems:

it is important to utilize all available information to estimate the fuel required for the particular flight and to flight plan in a conservative manner.

As does other training material:

...in any event, gauge indications of fuel quantity should always be cross-checked - on the ground by visual inspection, which may require 'dipping' the tanks - and in the air by comparison with indicated fuel flow (if available), flight plan expectations, or previous experience of proven fuel usage under similar flight conditions.

— General Aircraft Technical Knowledge, tenth edition (2007, ISBN 0-9583373-7-3)

We have the technology

The technology to provide accurate fuel consumption information already exists in light aircraft with fully digital panels ("glass cockpits"). The Garmin G1000 for example can provide a calculated value of fuel consumption alongside numeric tank quantity gauges [ref page 91]:

Calculated Fuel Used (GAL USED)

Displays quantity of fuel used in gallons (gal) based on fuel flow since last reset

Based on the mid 90's introduction of the Garmin G1000, it's a reasonably safe guesstimate that most light aircraft manufactured since the mid 2000's have come factory with glass cockpits with these features (I can't find exact figures on this though).

A lot of aircraft are old however - as in circa 1975. This is partly due to a huge downturn in light aircraft manufacturing in the USA in the 1980s and 1990s (due to accident liability concerns), and partly because older aircraft are considerably cheaper to purchase than their factory-new counterparts. Consequently, I've never flown an aircraft with a full glass panel in the four years I've been flying.

There's plenty of places to improve availability and accuracy of information in older cockpits with analogue instruments, and likely improvements to make in fully digital cockpits. Unfortunately this is not the kind of hobby where the CAA or FAA is ok for me to whack an Arduino and a digital flow meter on the fuel line; every piece of equipment has to be certified, and all work done by certified aircraft technicians.

This project will have to suffice until I can find a glass cockpit aircraft to fly. In any case even with the latest technology, I'll still be using a pen, paper and wrist watch as well.

Stephen Holdaway

Stephen Holdaway

Discussions

Become a Hackaday.io Member

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.

Thank you for your long answer. So as I understand now, because of the high importance of the fuel, the time is just another redundant piece of information you use, because you want and have to use any information possible, to monitor your fuel usage.

Now this makes much more sense to me.

Are you sure? yes | no