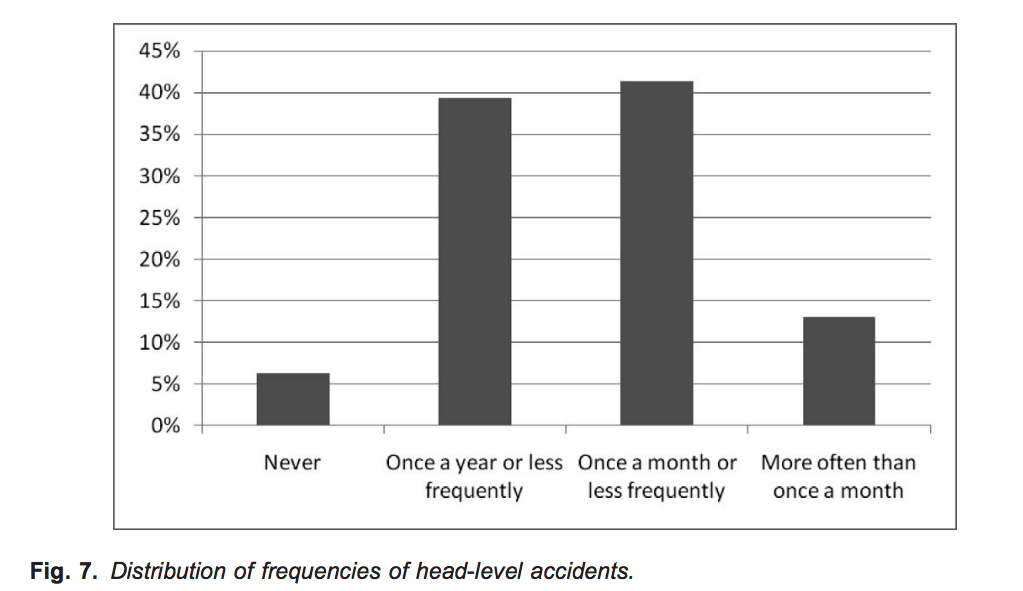

Problem: People who are blind and visually impaired face a huge number of mobility related head injuries.

Source: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/609b/3d62282eaa5c2e4a89c803c0b401a789e27d.pdf

Other Methods

Physical canes and sonar devices are useful, but provide limited information. Both are only measuring one point at a time.

A camera has multiple points and provides lots of informations, but unless you have stereo vision, the multiple points still do not measure depth. Without stereo vision, a pillar directly in front of you would be indistinguishable from a distance skyscraper.

Our Device

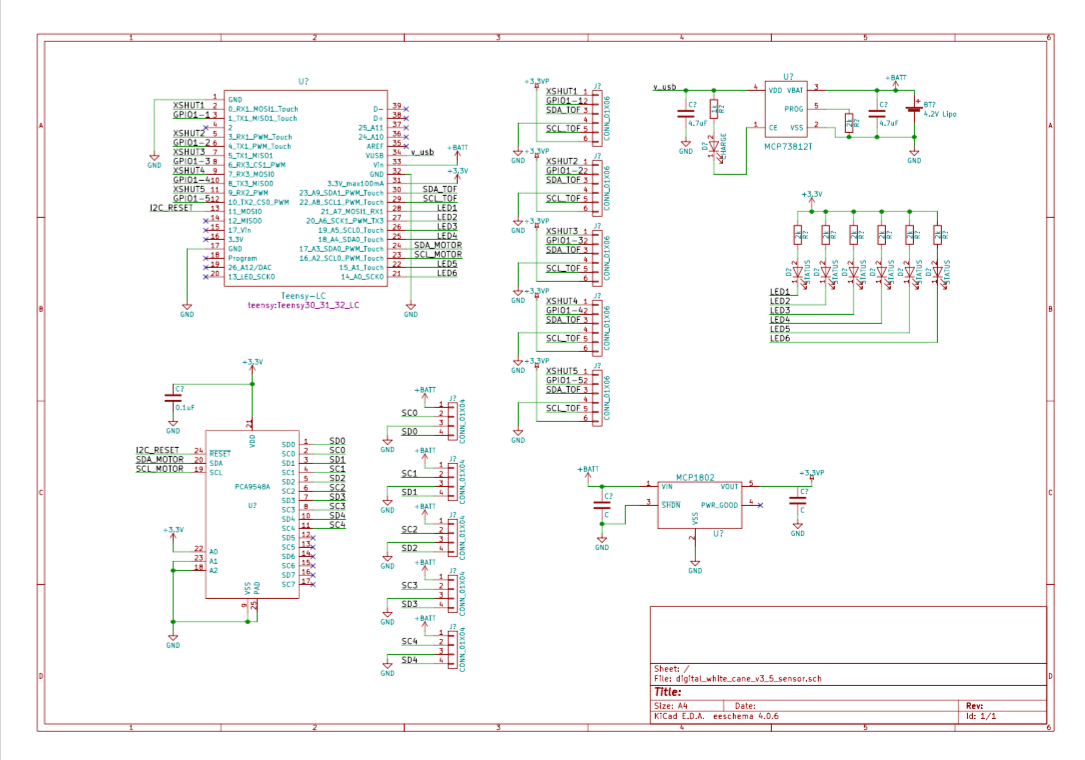

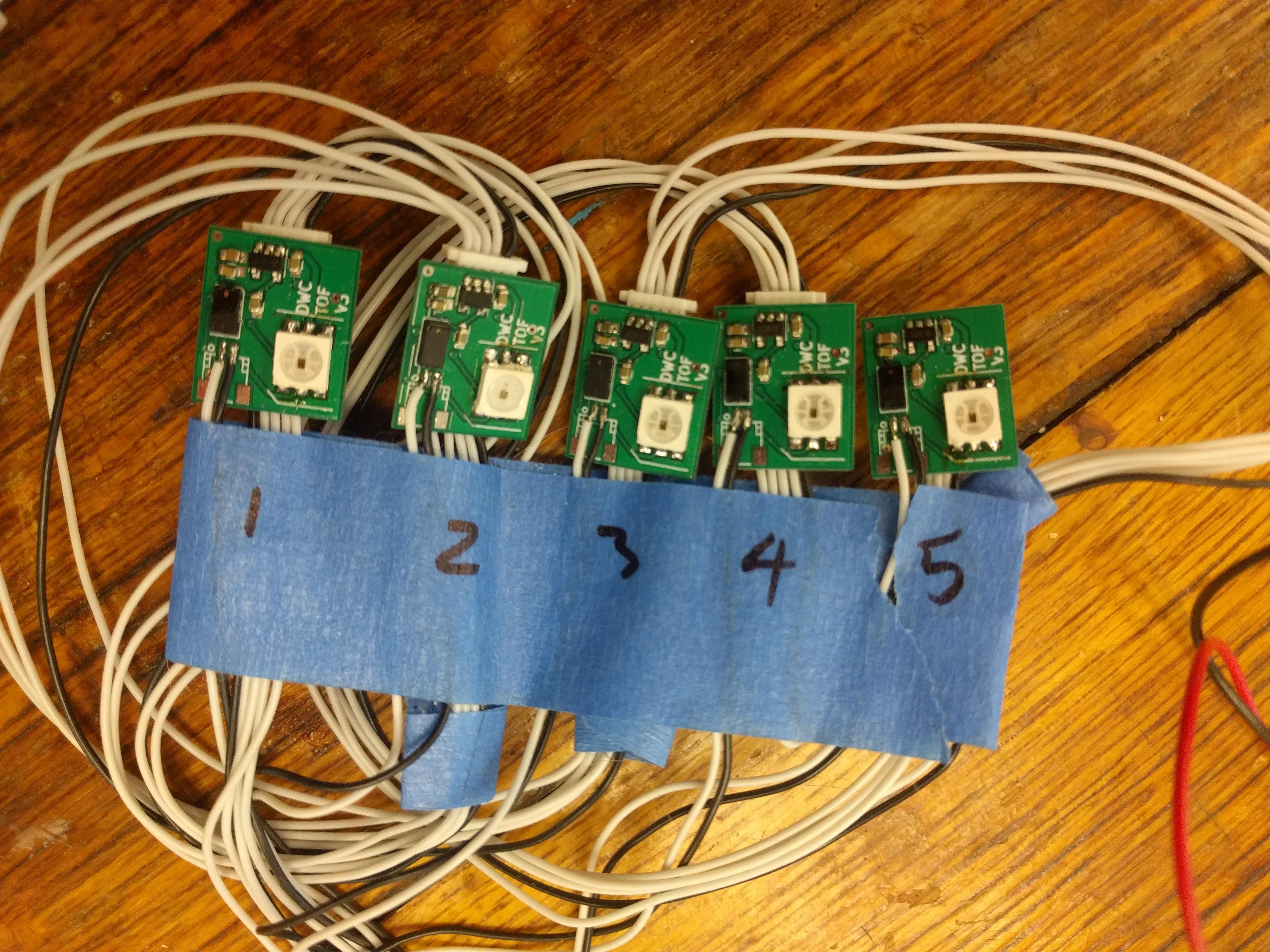

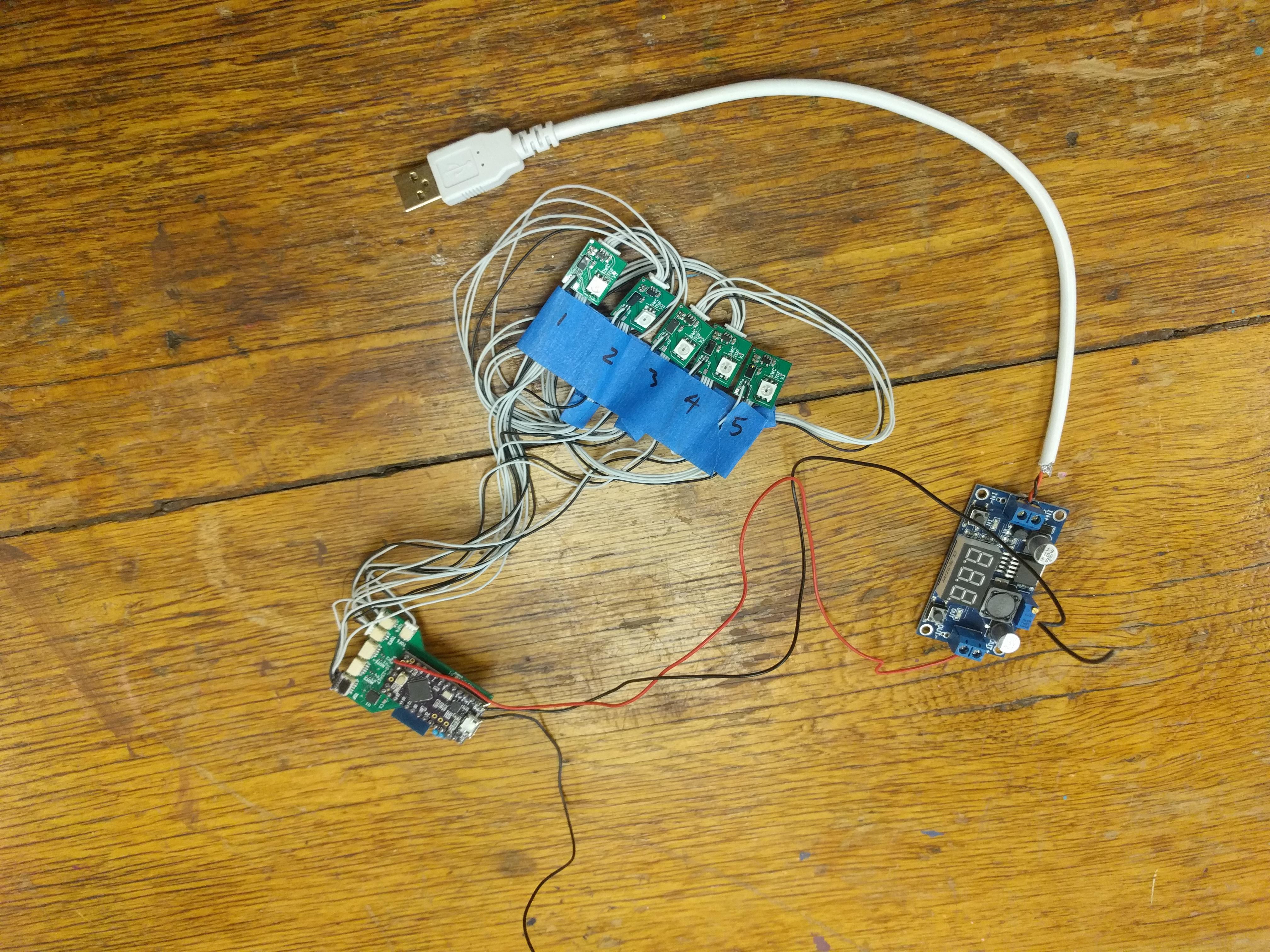

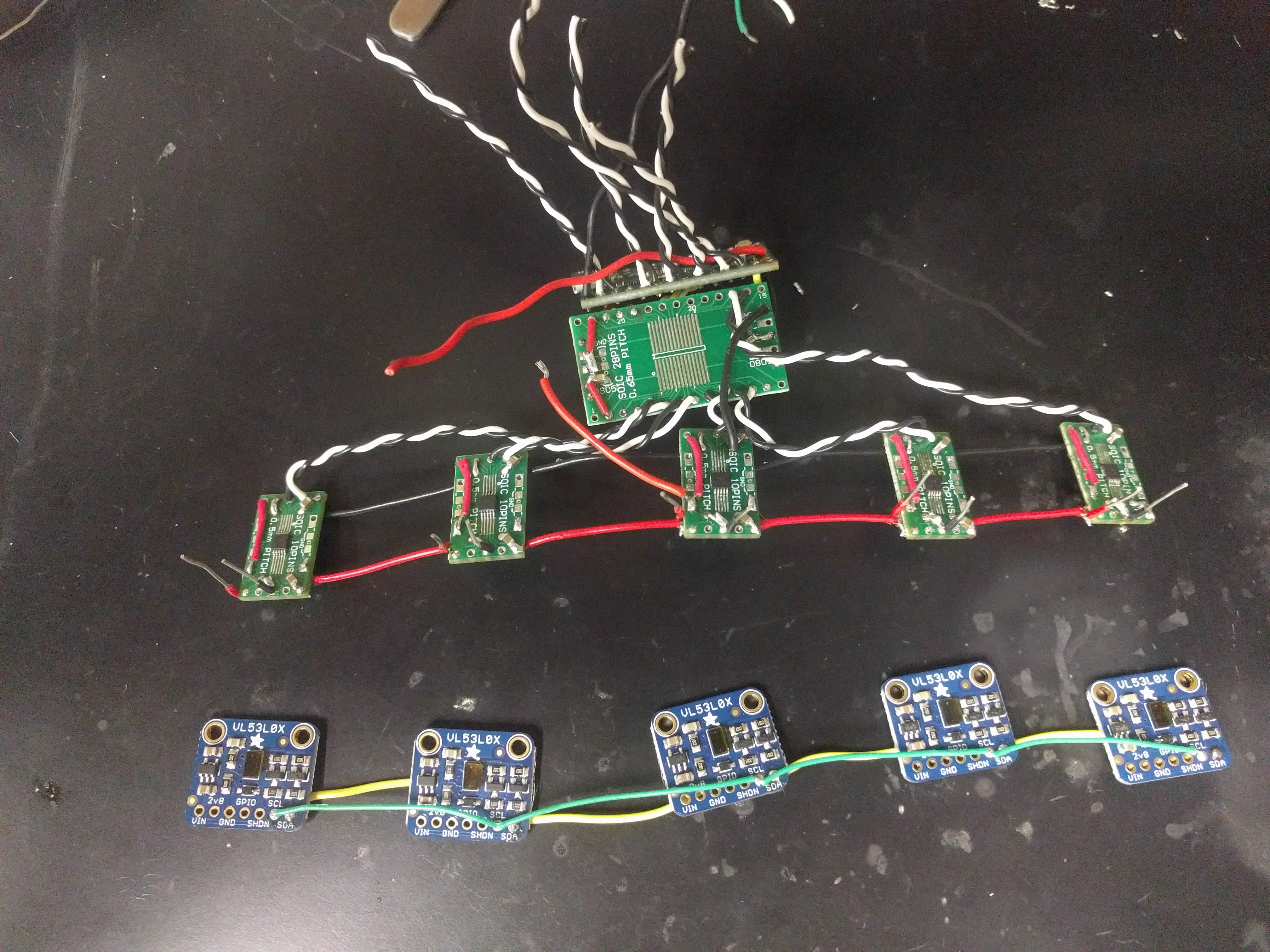

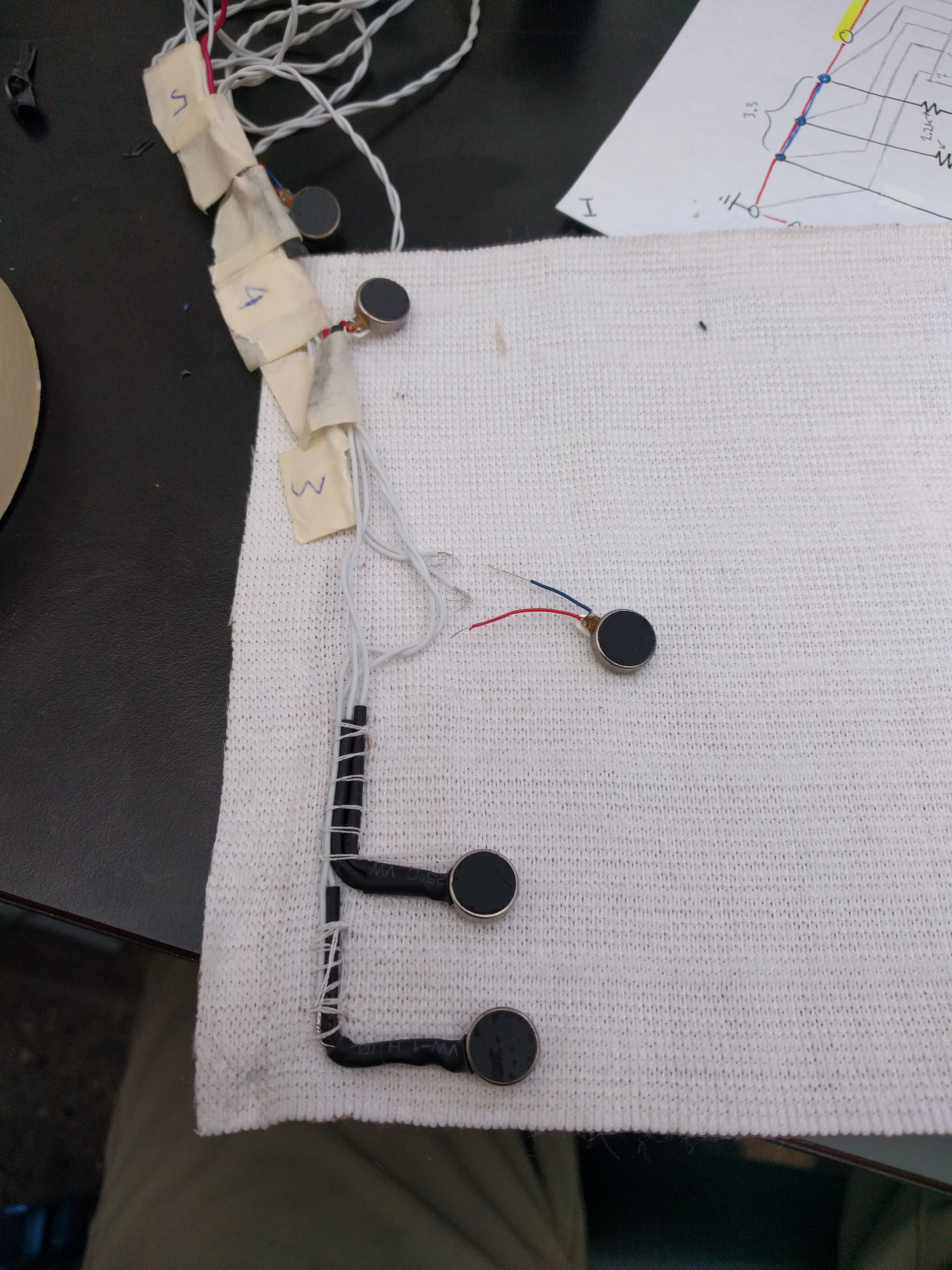

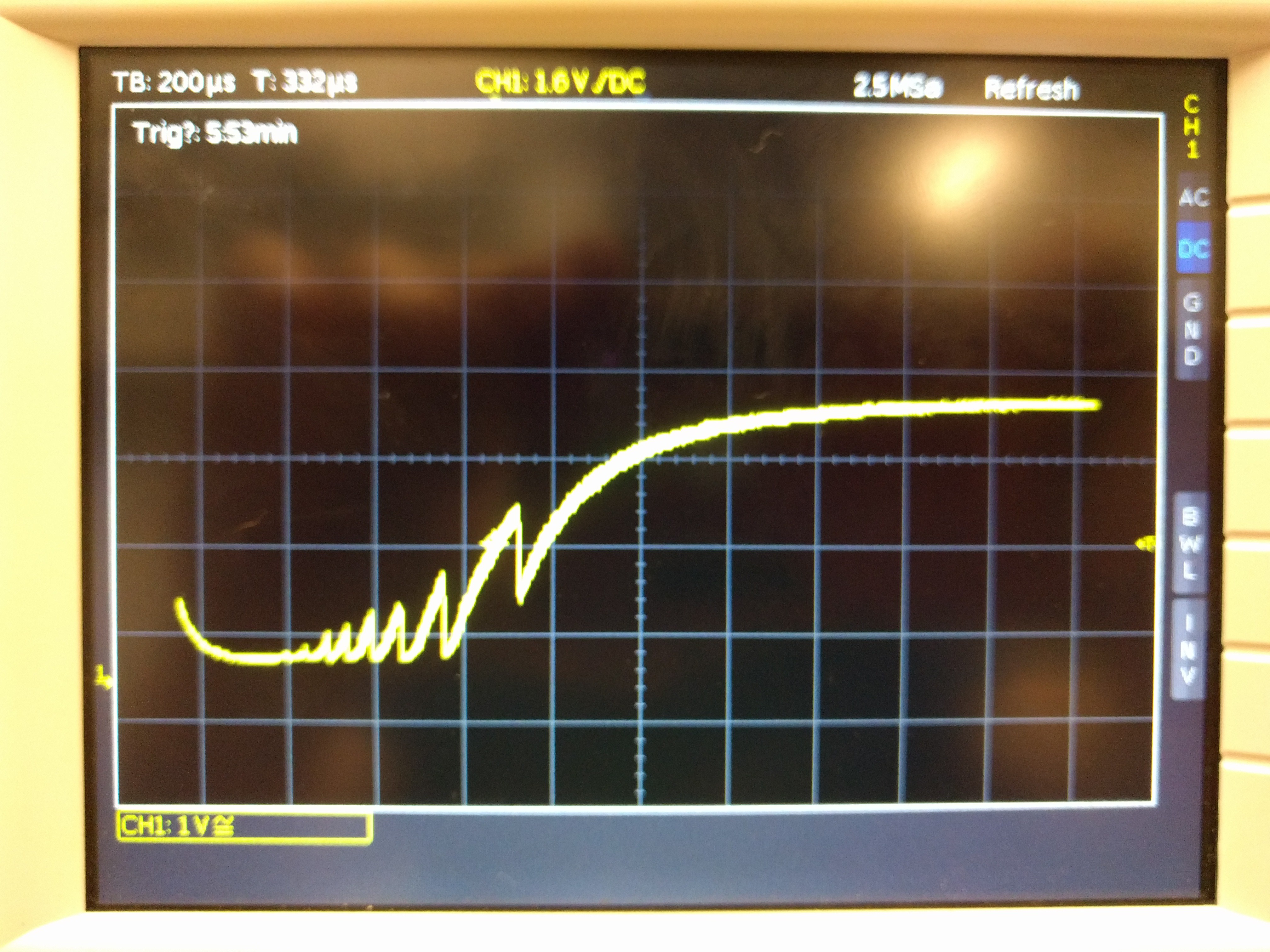

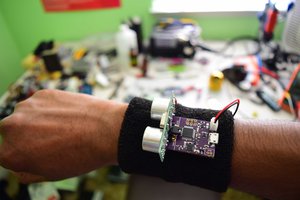

The Digital White Cane delivers immediate data and depth from multiple directions simultaneously. This technology wasn’t possible before ToF LIDAR tech. In the past, LIDAR was as big as a truck and very expensive. We’ve created a lightweight and effective solution.

Cost

As 87% of the world’s blind live in developing countries (ref below), we endeavored to make a device that was inexpensive and easy to replicate. When produced on a mass scale, our device is projected to cost less than $30 for materials and assembly.

R. Velázquez, Wearable Assistive Devices for the Blind. Chapter 17 in A. Lay-Ekuakille & S.C.

Mukhopadhyay (Eds.), Wearable and Autonomous Biomedical Devices and Systems for Smart Environment: Issues and Characterization, LNEE 75, Springer, pp 331-349, 2010.

Our First Real Life Test with Mary

Big Changes for Our Latest Device

George Albercook

George Albercook

This turned out to be awkward to put on. When putting on a shirt, it's surprising how much it helps that the sleeves are connected to the rest of the shirt. It's similar to fastening your own bracelet. One arm is less usable.

This turned out to be awkward to put on. When putting on a shirt, it's surprising how much it helps that the sleeves are connected to the rest of the shirt. It's similar to fastening your own bracelet. One arm is less usable.

Christine

Christine

Josh Cole

Josh Cole

Hi im working on the same Project !

https://hackaday.io/projects/hacker/251873

Regards

Peter